“This is where play comes in especially creative or ‘free play’. One of the qualities of play in higher primates, as observed in the wild, is its balance between improvisation and rule-governed behaviour. In fact, playing is the improvisational imposition of order on events.”4

“There is also no doubt that play must be defined as a free and voluntary activity, a source of joy and amusement. A game which one would be forced to play would at once cease being play.”5

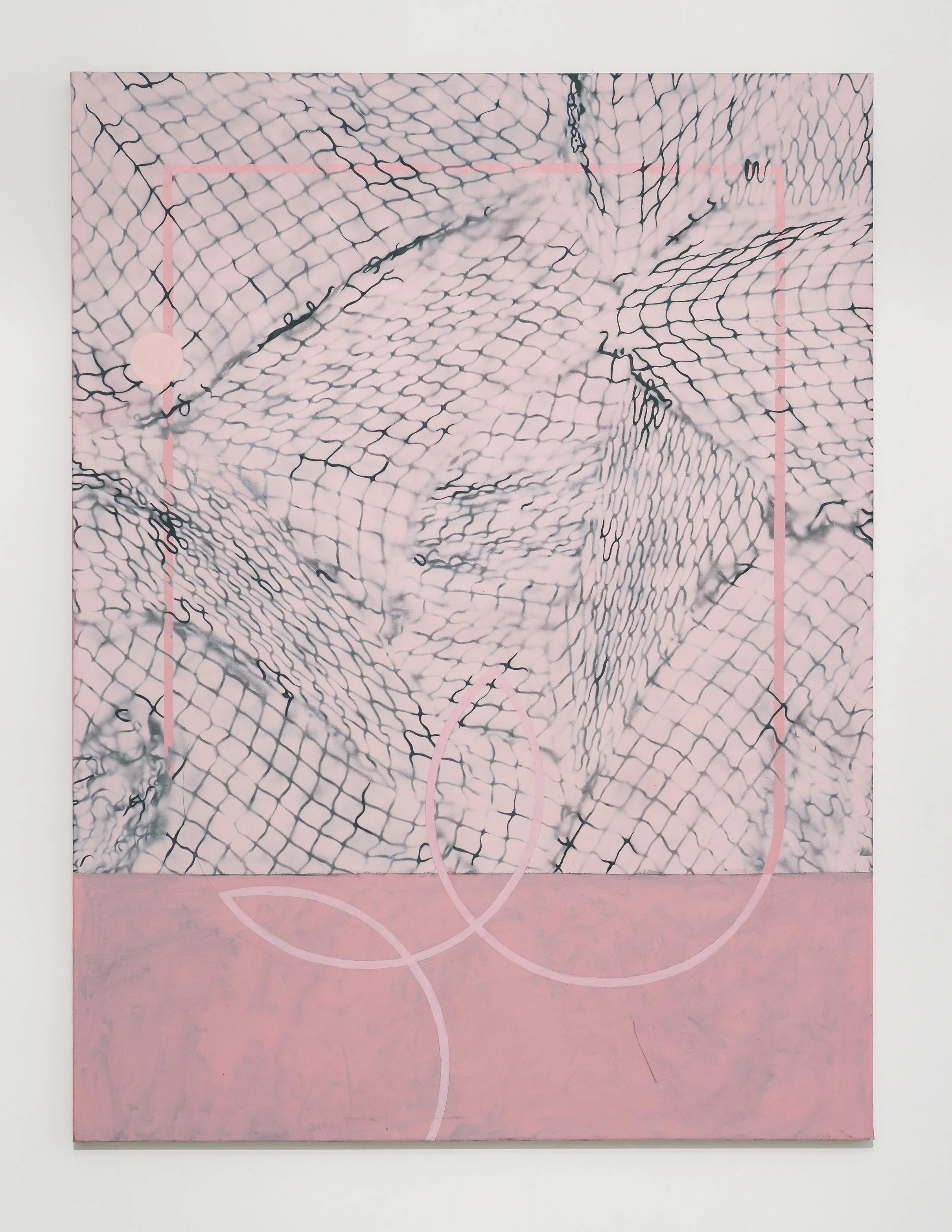

There’s an unmistakable fluidity in Michelle Furlong’s installations, a state of flow that can only be attained with certain types of unbridled play. The body becomes loose and malleable, enmeshed and at one with the space or field of activity. Furlong arrests this moment for us to observe and feel with our entire being. In her work, she fragments, distorts, casts, burns, and shellacs the chance encounters of play, freezing bodies ritually communing through movement to give them new gravitas and weight.

One of the first games I remember playing as a child is a round of ticktacktoe against a caged chicken in Chinatown. A family friend, who also happened to be my father’s gallerist in New York City, brought me to face-off against the prize-winning bird each time we visited. No matter how hard I tried to beat the Mott Street fowl, it always won.

In my early bouts with the chicken, I learned that play, much like art, is a dance between freedom and structure. Back then, my connection with the chicken felt like a magical event, but today the closer I look, the more the mystery has faded away. The chicken had to be following instructions somehow, like a dog responding to certain cues for treats. Right?

I recognize a similar sense of tension in the projects that have led Furlong to this exhibition-cum-game she’s titled Playing-Body. Take for example the kinesthetic vocabulary in There’s A Lot You Can Do With A Hammer (2021), a collaboration with Stephanie Creaghan presented at Tap art space in Toronto. There, an informal playground was created out of a parking garage turned exhibition space in an alleyway. Some rules for the installation were set ahead of time, but others were changed on the fly. In the repurposed structure, Furlong constructed a site-specific environment conducive to improvisation.

The term “hammer,” as a slang word, is used in sports to describe the act of defeating someone very thoroughly or decisively, as in: “they hammered the other team 45-10.” Furlong’s approach to transforming materials in her practice is much less brutal. Tactful, she allows her sculptures and installations to fail in ways that reveal their inner colour. Some sort of sacrosanct truth emerges in a constellation of Astroturf, free will, and polyester jerseys.

There is also a recurrent phenomenological crisis to Furlong’s version of play. This echoes how queer feminist theorist Sarah Ahmed revisits Heidegger’s analogy of the hammer as a ready-to-hand object—something we see through the task we are engaged in and not necessarily for the explicit properties it has as an object. Ahmed reframes this shift as a moment of embodied failure:

"In other words, what is at stake in moments of failure is not so much access to properties but attributions of properties, which become a matter of how we approach the object. So if I state, ‘‘The hammer is too heavy,’’ then I mean, ‘‘The hammer is too heavy for me to hammer with.’’ The moment of ‘‘non-use’’ is the moment in which the object is attributed as having properties, and it is the same moment in which objects may be judged insofar as they are inadequate to a task, the moment when we ‘‘blame the tool.’’6

Furlong does not blame the tool, but she does place it in a state of experiential suspension that no longer allows it to exist outside of consciousness. She de-naturalizes the phenomenological tissue woven between the ball, the net, the bat, the team kit, the long jump sand pit and the reaching hand or the outstretched foot. By intentionally failing the system she allows us to observe plainly an otherwise invisible rulebook.

In Playing-Body, Furlong continuously generates new rhythms and rhymes depending on the perspective of the viewer. This liminal zone, full of shifting conceptual possibilities and material potentialities, conjures the magical aspects of play. Just as the pre-eminent theorist of ludology Roger Caillois once speculated that play removes the very nature of the mysterious by exposing and expending secrecy through its codified and institutionalized nature, Furlong reinjects uncertainty into gaming by calling upon objects and symbols of divination, luck, and chance.

Each time I return to Furlong’s body of work, each time I pick it up to play again, a comforting sentiment of fortuitousness arises. I am reminded of the figurative hammer I hold in my hands, the tool I might use to play a sport. I feel its shape and mass, its ability to effortlessly oscillate between an awkward appendage of my body or a faultless extension of it. In Playing-Body, the striped soccer uniform I recognize as an inherent part of my childhood identity is both made familiar and foreign. Blurring the lines between this individual and collective experience, I share with Furlong in the awe at the joys of play.

Perhaps this ineffable sense of pleasure is what continues to linger most in my obsession with the ticktacktoe chicken. All my interactions with the fowl concluded with the same result: my loss at a simple game of X’s and O’s. Even with this foregone conclusion, I kept returning to play. An ardent competitor, but mostly driven by a love for the game, in all its beautiful complexity, I was drawn to the board. Just in case I might win, this one time.

5. Roger Caillois, Man, Play and Games [Trans. Meyer Barash]. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2001, page 6. 6 Sarah Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology, Durham : Duke University Press, 2006, page 49.

Didier Morelli Author